The Daylight Award Community

Mandana Sarey Khanie

FEATURE

What does daylight mean to you?

Daylight is an architectural element that brings new values to the space. It creates a vast palette from which the spatial experience can be drawn. To me, daylight means health, feel-good, hygiene, and freshness. 99% of human history, we have lived outside the cities and have been exposed to daylight. By 2050, this will dramatically change, and up to 70% of the population will live in denser cities where access to daylight becomes a rare possibility. In such a short amount of time, our bodies need to adapt to the conditions of living in the cities and spending 90% of our time indoors. Therefore, to me and for all of us, daylight is an essential remedy for healthier living.

How did your interest in the subject arise?

What interested me primarily in working with daylighting was the architecture itself. When I started my studies as an architect-engineer, I thought I would be looking at a profession that assists people to realize their imagination in the shape of forms and spaces they could occupy. Little did I know that creating these imaginary forms is entering into an architectural “multiverse.” Like the initial meaning of the term, an architectural “multiverse” is what I would describe as a phenomenon comprising many dimensions that are not directly observable. However, we are directly influenced by them.

Walking through the various buildings of Vitra Campus, Bazel, Germany, was where I got primarily inspired by the effect of daylight on building forms and volumes outside and inside. The subtle and smooth transitions of light in Tadao Ando’s conference pavilion, the large volumes of light and dark in Gehry’s design museum, and the linear collisions of transparent daylit surfaces, glossy and diffuse surfaces in Zaha Hadid’s fire station. In this architectural experience, I realized that daylight, by far, is a vital dimension of buildings.

Later in my studies at Chalmers Technical School in Gothenburg, Sweden, I attended a workshop called “Designing in the dark” organized by Marc Dujardin, Professor in Universal Design and architectural anthropology, Faculty of Architecture, KULeuven. The core exercise was to realize the importance of light and its interaction with different materials and surfaces on how we see and how such design decisions could affect people and their behavior with various visual capabilities or impairments. Finally, in Light in Alingsås, I met two inspiring lighting designers, Olsson & Linder, who tried to make people’s living spaces more safe and present and create a sense of belonging using only lighting as a building material. These three experiences led me to dedicate my career to learning more about daylight, how it affects us and how we can integrate it best in our living spaces.

How do you work with daylight in your research?

In my research, I do experimental work in controlled or semi-controlled environments where I can explore the effect of light on human subjective and objective responses. Human responses in interaction with the building have direct and indirect consequences on how the space is used and how the building performs. And in a loop, the mentioned interaction influences our health, wellbeing, and productivity. What interests me most is how we respond to exposure to daylight and what we can learn to better understand and meet human needs in buildings. I work towards bringing my findings into simulation tools; hence daylighting simulation is also a large part of my research and educational work.

Which project/publication describes your work the best?

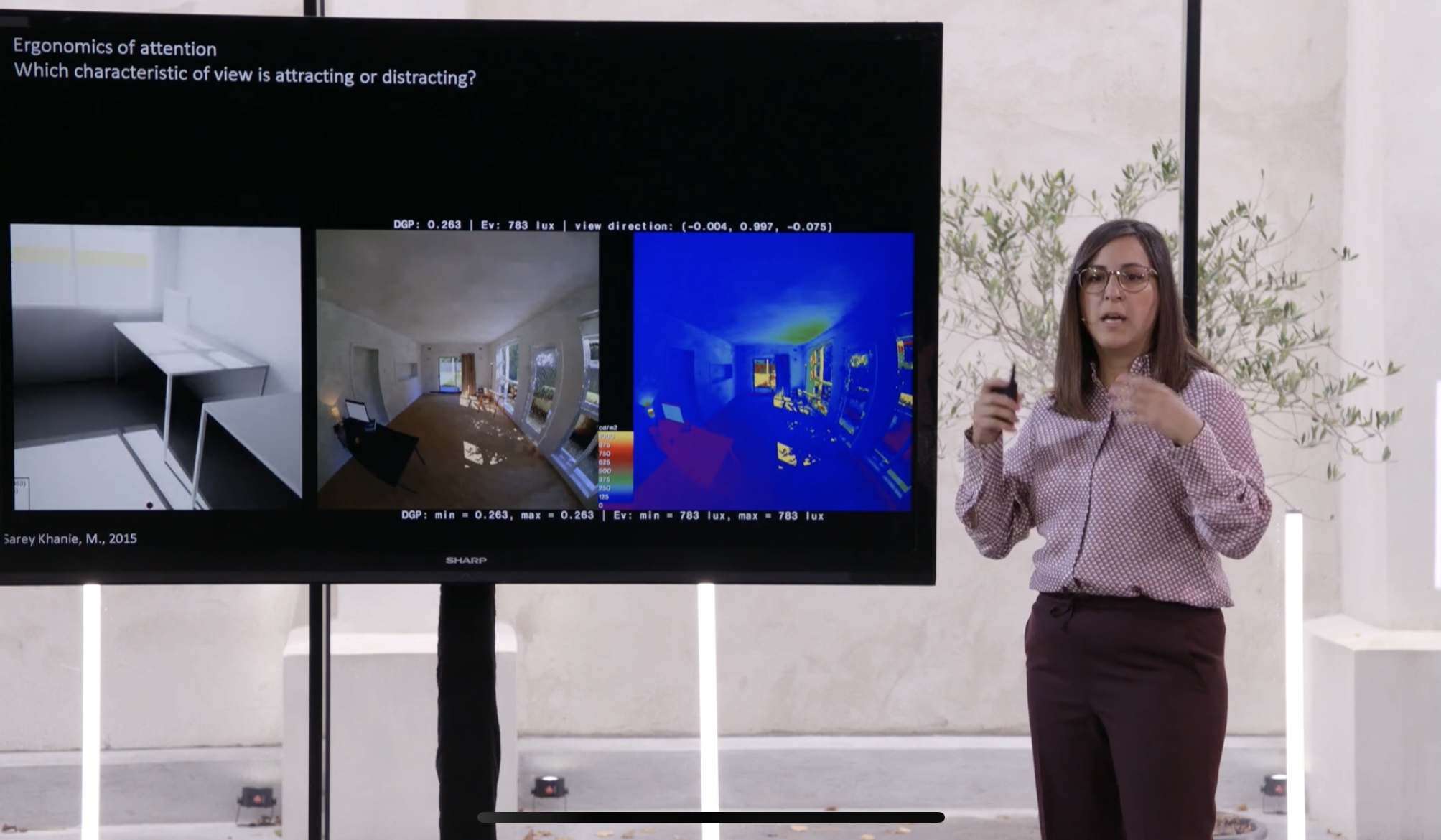

Gaze-driven photometry for human responsive spaces was my Ph.D. project, where I started exploring the relationship between daylight conditions and reflexive movements of the eye. Sight is undoubtedly the most dominant sense, with up to 70% of all our sensory receptors in the eyes. A plethora of cues are constantly being introduced to the human brain through our vision. Coupling advanced lighting measurements and eye-tracking methods in a controlled environment, I studied the effect of light, task, and view on human gaze movements and subjective responses. Using the developed gaze-driven methodology, exposure and characterization of daylight at the ocular and individual levels is possible. I have continued working further on the topic in years proceeding. I am also actively involved in realizing a platform for a harmonized education in daylighting for students and practitioners. NLITED (New Level of Integrated TEchniques for Daylighting education) is an educational project funded by the European Erasmus+ program. Together with Federica Giuliani (IT), Niko Gentile (SE), and Natalia Sokol (PL), we built an educational platform and summer school program on daylighting in buildings.

According to you, what is the most important focus for the future?

A better understanding of basic human needs in buildings can lead to solutions for creating a healthier and resource-efficient society with impacts for generations to come. Human health and wellbeing are the essences of sustainable and long-term solutions. Such solutions include appropriate and smart integration of daylight in buildings, reducing energy consumption towards low carbon solutions, and developing multi-domain solutions, where all aspects of indoor climate are considered.

I have been fortunate to have many inspirational people on my journey in working with daylighting, from ambitious architectural lighting designers aimed at changing people’s living spaces for the better to energy efficiency and sustainability gurus that inspired me with their passion for creating a better world. Professor Maria Nyström taught me to think in extreme conditions where basic needs are difficult to satisfy. The need for sustainable and subtle buildings with minimal resources is the way forward. Professor Monica Billger connected me to the daylighting research. I have been directed by Dr. Jan Wienold and Dr. Jens Christoffersen and their scientific approach to daylighting. Professor Marilyne Andersen not only taught me the importance of daylight for our future but also taught me perseverance. Her passion for creating healthy living spaces is an ongoing energy that inspires me professionally and as a female researcher in the building sector.